The Dutch Revolution of Total Football!

Prologue!

Anyone who was young in the late 1960s and early 1970s was surely influenced by the myth of Dutch football, the great protagonist of that cultural revolution that in that period, up until the 1960s and especially the early 1970s, was also transmitted to football.

A cultural revolution of the young, of the new generations who want to change everything, from Mexico, to Chile, to the world of Ultras, many things are changing in Europe but also in Latin America and North America.

Slowly a new generation is taking hold at a political and social level and culturally this youth revolution is also transmitted to the world of football. And the best fusion between football and society in this area is realized in Holland. Dutch football, the great Holland, total football is the great protagonist of football in the early Seventies and obviously also of this article

Perhaps it would be more correct to speak of a rebirth of Dutch football according to some because in reality Holland had already created its own rather positive tradition in the world of football well before the seventies.

* * *

The Netherlands won three Olympic bronzes at the beginning of the twentieth century, in 1908, 1912 and 1920, and in 1924 they achieved fourth place, so we are talking about a nation that was very strong in football at the dawn of this sport when there was no World Cup yet and especially before Paris, the edition of the games in which football entered its modern phase and slowly became a mass sport.

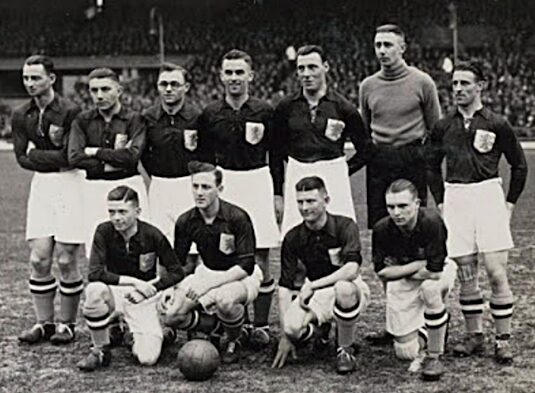

Holland Team at the World Cup in 1934!

Even in the 1930s, Holland performed well in the first two editions of the World Cup, reaching the eighth finals in 1934 and 1938. They would participate again in the 1948 Olympics, the first after the Second World War, holding their own against the United Kingdom, losing only 4-3 in the first round. From then on, however, Holland disappeared from international football.

This first golden age of Dutch football is due above all to the influence of the British school, English in particular. Between 1908 and 1913, therefore at the time of the first two Olympic bronzes, the Dutch national team is coached by Edgar Chadwick. Subsequently, between 19 and 23, it is coached by Fred Warburton, another Englishman, and again his compatriot, William Townley, will lead the team to the 1924 Olympics.

Between 25 and 40, so for a long period, Holland was coached by Bob Glendening. Later, between 47 and 48, so at the time of the last Olympics in which they participated, on the bench sat one of the great masters of English football of the time, Jesse Carver, who then in the 50s would also coach Juventus and Inter in Italy.

These links between Holland and England are actually easily understood even outside the sporting context. Just look at the crating and then realize on a historical level that the ports of the Netherlands were a fundamental landing point for the English on a commercial level for continental Europe.

So right from the start there are cultural and economic ties between the two countries, which favor as we have seen many times, the transfer of football and its knowledge, the English know-how, which moves a bit all over the world following the trade routes. This British influence, however, fades in the post-war period, after the Second World War, and a small Eastern European influence slowly emerges.

In fact, between 1957 and 1964, Holland was coached by a Romanian, Elek Schwarz, and then, between 70 and 74, by a Czechoslovakian, Fram Tisek Fadronc. Despite all these external influences, Dutch football remained very conservative. At the beginning of the 60s, for example, all the teams in the local league still played the WM system, which was invented as we know in the 30s, so it is very ancient, very old and now outdated, practically in every part of the world.

Professionalism officially arrived only in 1954 and with many difficulties, especially because of the former president of the Football Association, the KNVB, who between 42 and 52 was Karel Lozzi. Lozzi was strongly opposed to professionalism, he believed that football, like the English tradition, should be an amateur sport for the predominantly upper classes.

This is indicative of the conservatism and cultural backwardness in Dutch football, because these thoughts that Lozzi had in the 1940s were by then outdated in England, as we know, by the end of the 19th century.

It should be added that Karel Lozzi was not only a conservative in sports, but also in political life. Only in the 70s, that is, after his death in 1959, it was incredibly discovered that during the Second World War he had been a collaborator of the Nazis during the military occupation of Holland and that he had participated in the arrest of some Jews who were then deported and killed in concentration camps. Lozzi was a Nazi and an anti-Semite.

As we were saying, football has been professionalized in Holland only since 1954 and this is at this time only on a formal level. In fact, professionalism still has to take hold over time. In previous years, however, this reform had become necessary due to the flight of many Dutch talents abroad in order to make a living from football.

Fas Wilkens in action

The first, the most important, was the left midfielder of Xerces Rotterdam, Fas Wilkes. He was the first great champion of Dutch football. When in 1949 he left Rotterdam to move to Italy to play for Inter, his was a historical case.

He is the most important footballer to have made this move abroad, although not the first ever. Wilkes will become a star of Italian football, he will tour European football for a few years, but above all when he left Holland he was excluded from the national team because he was no longer an amateur footballer but a professional.

The crisis of Dutch football after the 40s can also be explained in this way here. Many great footballers decide to go abroad to become professionals because in the Netherlands it is not possible, but they are excluded from the national team which thus has a great drop in performance and disappears at an international level.

In addition to Wilkes, striker Bram Appel, one of the best Dutch footballers of the time, also moved abroad in 1949 to play in France at Stade Reims. At the same time, another striker, Bertus de Harder, also moved to Bordeaux.

Bram Appel

The following year, striker Andre Rosenborg would move to Fiorentina and at the same time, midfielder Kees Rivers would move to Saint-Étienne. In 1952, another Dutch star left the country, striker Bart Carlier, who moved to Cologne in Germany. In general, the entire Dutch society of this period was deeply conservative.

Since 1959, the Christian Democrats have been in power, especially the Catholic People’s Party, but sometimes we also see the Anti-Revolutionary Party in government, a rather disturbing name for a party that is in fact Christian Democrat but Calvinist and not Catholic.

To give you an idea, Holland is so conservative at this stage that it even has two Christian Democrat parties for the two different religious confessions. Obviously, as has happened in other cases, it is from the Sixties that things begin to change, with the cultural revolution that comes precisely, obviously, from the United Kingdom.

The Dutch epicenter of this youth revolution is obviously the capital, Amsterdam, which is a culturally very lively city. The symbol of these new young people who want to change things is an anarchist movement, not actually explicitly politicized as it is in other countries.

They are called the Provos, or the provocateurs. They are in charge of carrying out forms of social, rather than political, provocation that are very over the top. As I said, they are not explicitly characterized by a left-wing political vocation, even if it is obvious that most young people in Holland at the moment are politicized towards the left.

The Provos, however, carry forward a social ideology that is against consumerism, non-violent, and therefore deeply pacifist, and also ecological. One of the symbols of their protest is in fact bicycles.

But they are only the most visible vanguard of a youth movement that is establishing itself as a revolutionary force, also in the Netherlands. In June 1966 there are very strong student protests in Amsterdam. This leads to an evident crisis of the Christian Democrat governments and to the decision of Dutch politics to respond to these youth protests in the most unthinkable way possible. That is, instead of repressing for once, we welcome.

Holland starts talking about new liberalizations, new youth policies. The population wants to change and then the government says okay, let’s change, let’s improve things, let’s open up to the world, the country quickly becomes much less conservative than before.

Joopten Uyl – Dutch Prime Minister!

It is a small phase of great social optimism that leads in 1972 to the election to government of Joopten Uyl and his Labour Party, a social democratic formation that at this stage of its history is characterized by a program that includes great promises of social reforms and the fight against inequalities, perhaps the most left-wing government in all of Dutch history.

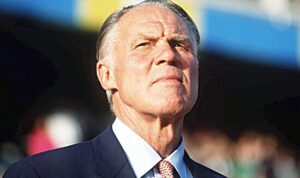

And it is precisely at this moment, simultaneously and without any precise social or political connection between the two things, that in the same place there is also an incredible reflux of football. A new way of playing is established that has as its epicenter an important club, obviously, from Amsterdam, Ajax. Starting in 1965, on the bench of Ajax sits one day a coach named Rinus Michels.

His idea of football is deeply offensive, but above all it involves a great revolution in the concept of role and position on the field. The Dutch press renames Ajax’s way of playing as Total Football, that is, total football. It consists in overcoming the rigid traditional division of labor between defenders and attackers, that is, the idea that the defender must only defend and the attacker must only attack.

Everyone must participate, in their own way, in the different phases of the game. How and why total football was born is still a matter of debate today and on which the final word has not yet been placed. Let’s say that the tradition of offensive football in Ajax arrives as far back as the 1910s, thanks to a coach, obviously, English, named Jack Reynolds.

Reynolds is a supporter of that passing game. His idea is precisely to play a football based on passing and the search for offensive play, a new philosophy that renews the elementary football that was played at the time in Holland and above all brings to Ajax a new idea linked to the youth sector, that is, that the youth team should play in the same way as the senior team to facilitate the transition of the boys from the youth teams to the first team.

This attacking tradition of Ajax football, which derives from Scottish football, was renewed by Vic Buckingham, another English coach who arrived here in 1959 and coached Ajax until 1961 and then again between 1964 and 1965.

Michels is therefore the heir of this tradition, which in the meantime has spawned other children around the world, one obviously being the Wunderteam of Austria in the 30s, we talked about it in episode 34, and another being the Aranixapat, that is, the golden team of Hungary in the 50s, you can find out more about that story in episode 58.

But journalists, historians, sociologists have also identified other cultural influences that have influenced the birth of total football, which are typically Dutch. For example, the fact that total football is focused on the use, on the optimal management of space on the pitch.

And this would be, according to some, a derivation of the Dutch culture that is used to dealing with a very limited physical, geographical space. The Netherlands are mostly below sea level, so they were built, urbanized, planned, in order to fight against these limits of nature, precisely spatial limits. In addition, some point out that before total football there was total architecture.

The so-called Amsterdam school, that of Michael de Klerk, which at the beginning of the twentieth century changed the way of conceiving urban planning and city architecture. De Klerk argued that each single element of the city should not be conceived as a stand-alone, but as part of a broader concept, a total concept of the city. And this transposed to football a few decades later is in fact Total Football.

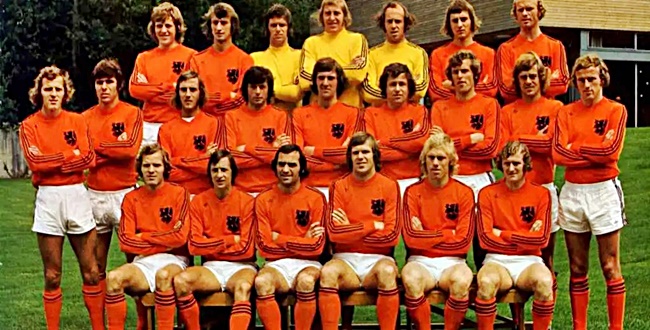

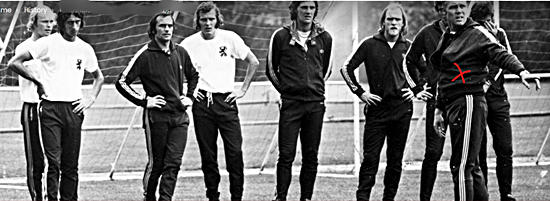

Added to this is the fact that, as we have anticipated, total Dutch football would not have been possible without the youth revolution of the 1960s and 1970s. The players of this new Holland, and of the X in particular, were marked by many breaches of convention, of the traditional rules of society and of football. For example, they wore long hair, something that had never been done before, and not only that, they wore numbers on their shirts that were not limited to one to eleven.

All these topics are well discussed in the book Brilliant Orange by David Wimmer. Wimmer presents many truly fascinating theses, on which, however,

I must admit, I am not entirely convinced, and I often find them a little forced, especially these connections between football, Dutch culture and art. There is, however, one aspect that should be underlined, that perhaps, rather than talking about the culture that inspires football, it would be interesting to do a reversal.

Football that inspires culture. As sociologist Frank Lechner says, Dutch football, in fact, becomes the first real form of self-representation of Holland as a society. A society that is reflected in football.

A company that from this moment on, from the early seventies, begins to perceive itself as a young and revolutionary company. A proactive company. In a more philosophical sense, Total Football is almost like a religion, because Rinus Michels wants total dedication from his players towards his ideas.

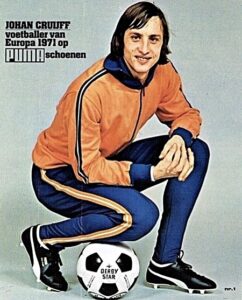

The fact of playing without fixed positions, focusing on passes, on technique, on the cohesion of the game, on the zone, on pressing, is above all an act of faith. And like every act of faith, like every religion, total football must have its prophet. Their prophet. His name is Johan Cruyff and he is the striker of this team. Officially he would be an attacking midfielder, but then on the field he is used by Michels mainly as a center forward. He is a withdrawn center forward.

He is the last heir of a tradition of atypical footballers that has already had among its main elements Matthias Zindler in Austria in the thirties and Nandori De Cuti in Hungary in the fifties. Cruyff comes from a very humble family, from a small neighborhood of Amsterdam. His parents had a fruit and vegetable shop, but he was orphaned by a panda at a very young age.

When the pander died, his mother had to sell the house and the fruit and vegetable shop. He had to abandon his studies to go to work, still very young, and help support the family. And at the same time he played football.

This very humble origin will be fundamental to understanding who Johan Cruyff will be in terms of football, but above all as a character, once he grows up. Because we are not just talking about an extraordinary footballer, an absolute champion who will win the Golden Ball three times in the seventies. The first footballer to win the title of best player in Europe three times.

We are also talking about a figure who revolutionizes the concept of a professional footballer. Cruyff will be the first footballer who is an entrepreneur of himself. For example, he goes to negotiate directly with the Ajax managers to get increases in his contract. His idea is if the team plays well, if the team wins, I am a protagonist in this team and I want to be paid more because I deserve it. Every time he and his team achieve success, he goes to the managers to collect money. And he doesn’t do it alone.

He is accompanied by his father-in-law because Cruyff married a girl whose father is Core Coaster, that is, one of the most important and richest diamond traders in the world. In fact, we are talking about the first footballer who goes to negotiate salary increases with the club’s directors, bringing along an agent. Not only that.

He also wants to get paid when you play for the national team because he says football is my job. I play and therefore I work. If football is my job I must be paid when I play for the club but also when I play for the national team because I am working there too.

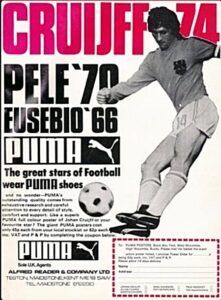

And he will be one of the very first footballers to have a personal sponsor. In the 70s he made an agreement with Puma, a large German clothing company. This will also create a big scandal in view of the 1974 World Cup because at that World Cup Holland will show up with a shirt sponsored by Puma’s great rival, Adidas.

At the time, it was not yet possible to put the logos of private companies on the shirts of national teams or even clubs. So Adidas found a very original idea to get its logo purchased on the Holland uniform for the World Cup. It did not put the logo itself, but it would put its three characteristic black stripes on the shoulders and sleeves of the Holland jersey.

But Cruyff already has an exclusive agreement with Puma and cannot wear the Adidas logo. He refuses to do so and threatens not to go to the World Cup. This will force Adidas and the Dutch Football Federation to find an incredible solution. Holland will play with the jersey with the three black stripes of Adidas. Cruyff will wear a different jersey, still orange but with only two black stripes. The impact of total football on European football is devastating.

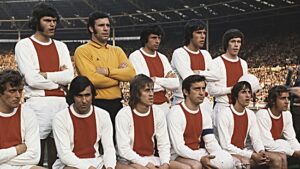

In 1969 this revolution took place. Ajax reached the Champions Cup final against Milan. They lost but showed that something was changing. The following year, the other great Dutch team, Feyenoord, reached the Champions Cup final and beat Celtic, who had won the European title a few years earlier.

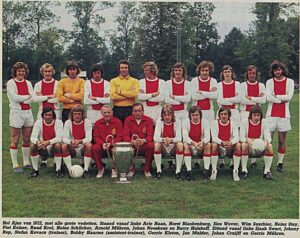

Between 1971 and 1973, Ajax won the European Cup three times in a row and more or less in the same period, as we have seen, Cruyff won three Ballon d’Ors. In 1974, just before the World Cup in West Germany, Feyenoord won another European title, the UEFA Cup.

Holland therefore presented itself at the 1974 World Cup as the big favorite. In reality, it must be said that in the qualification process the team coached by Frantisek Fadronc did not do very well, it dropped a little bit in terms of play and results. For this reason, the KNVB, the football federation, before the World Cup changed the coach, leaving the Czechoslovakian, and called Rinus Michels from Barcelona, where he had moved a few years earlier.

The maestro of total football must lead his team to win the most important title of all, the consecration of Holland as a football country, for the first time in its history. As you may have understood by now, when a team presents itself as the number 1 favorite in dispute to win a title, especially if we are talking about the World Cup, it almost always does not win.

And in fact the dream of the great Holland stops in the final against West Germany. The Dutch start very strong, destroy the Germans after a few minutes, penalty, score and take the lead. It seems like the beginning of a devastating victory for the Orange over the Home Pantones and instead Holland will not be able to make it 2-0. The Germans will regroup and win 2-1.

According to Dutch playwright John Timmers, the defeat in the 1974 final is the greatest trauma in Dutch history in the 20th century, after World War II and the flood of 1953. This is to make you understand how much Dutch society is shaken by this unexpected defeat. They thought they had fate on their side.

The youth, political, social and sporting revolution that arrives and consecrates itself and tells the world, here, things must change, and we will explain to you how the world must change. It is, according to David Wimmer, a sort of Dutch version of the myth of Camelot. The idea of a great revolution, of a great positive change for society that crashes right at the most beautiful moment.

Taking Timmers’ words again, who also mentioned the Second World War, we must remember that this final is between the Dutch and the Germans, that although West Germany is obviously no longer Nazi Germany, it is still the country that occupied the Netherlands during the Second World War. There is an unresolved trauma here, in Dutch society. The German occupation, which began in 1940, was devastating.

It caused over 205,000 deaths and the highest death rate per capita in the Western countries occupied by the Nazis. More than half of these deaths were Jews, victims of the Holocaust. One of these was an Ajax footballer, his name was Eddie Hamel.

The Holocaust is one of the stories we mentioned in episode 45, about football and the Holocaust. In a broader sense, the defeat in the 1974 final will be the crisis of the optimistic dream of the Holland of the 60s. Quoting the historian Bastien Bommelier, the Dutch national team was the product of an era that had invested everything in young people and their promise, and in the idea that things would be better if a new generation was in power.

The year after the World Cup defeat, in 1975, the economic crisis began that hit the Social Democratic government of Joop den Uyl. A crisis that was obviously linked to the oil crisis that was hitting the world. The Netherlands was in fact one of the countries most affected by the OPEC boycott because of its support for Israel in the Yom Kippur War.

In addition, new internal scandals emerge, there is the case of the independence of Suriname, many things put together that create a political crisis that brings down the government of Den Uyl, forced to resign in 1977, after which the conservative Christian Democrats will return to power. This idealistic Dutch dream therefore slowly crumbles, and at the same time the great era of Ajax after three consecutive European titles also crumbles.

Stefan Kovacs

Michels had already left to coach Barcelona in 1971, but the cycle continued under the guidance of a Romanian coach, Stefan Kovacs, who was one of the great innovators of total football, perfecting Michels’ work. However, in 1973 Kovacs also left and would go on to become the coach of France.

Georges Kneubel of MWV was hired in his place, but at the same time Johan Cruyff also left Ajax, who, having fallen out with the management, decided to join Michels at Barcelona, and there he would change the balance of Spanish football.

After the 1974 World Cup, the other great Ajax champion, midfielder Johan Neskens, also moved to Barcelona, forming the first great Dutch colony of the Blaugrana club. In 1975, three other pillars of the lancers left. Ari Haan went to Anderlecht, Horst Blankenburg to Hamburg and Johnny Repp to Valencia.

In 1976, Gary Myhren also left Holland and joined Betis. That summer, Holland, now under the guidance of George Knöbel, coach of Ajax, aimed to become European champions, presenting themselves as favorites at the European Championships, and instead, a real loser, they only finished third and the title went to Antonin Panenka’s Czechoslovakia. The swan song of the great Holland was the 1978 World Cup.

The national team is now under the guidance of Austrian Ernst Appel, the coach of Feyenoord, European champion in 1970. However, Johan Cruyff is not there, having decided to leave the national team due to a lack of motivation. The Orange remain a great team and the big favorite for the world title this time too, and this time too they will surrender in the final against the hosts, Argentina.

From here a new period of crisis for Dutch football will begin. In fact, until 1988 when they finally win a title at the European Championships, but that’s another story, Holland will never be truly competitive again. So the great Dutch fairy tale of the 70s ends here.

It’s true, total football hasn’t won any titles, yet it has changed world football. Zonal defence, pressing, no longer fixed roles on the pitch, all elements that Holland presents to the world and that from this moment on will become fundamental for all the tactical development of football in the following years.

Ultimately, however, Holland represents what the 70s were.

A brief, fascinating, exciting period of reforms, revolutions, youthful promises in great change, which perhaps did not achieve the results hoped for at the time, but which contributed to changing, in some ways for the better, in others unfortunately for the worse, the society of the following years.

Maybe it was not exactly the myth of Camelot, as David Wimmer said, but it certainly left its mark, melancholic but also concrete, in everyone’s life, and not just in sports.

Pjerin Bj

New York: May 5, 2025

____________________________

Sports Vision + Plus / Champions Hour in activity since 2013

Discover more from Sports Vision +

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.